How to Trademark a Business Name

Learn how to trademark a business name with our complete guide. We cover trademark searches, USPTO applications, and brand protection to secure your brand.

Trademarking your business name gives you exclusive legal rights to it across the entire country. It's a powerful tool that stops competitors from using a name that's confusingly similar to yours. By filing with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), you're not just registering a name; you're securing a valuable business asset tied to your specific goods or services.

Do You Really Need to Trademark Your Business Name?

Before you jump into the application process and start paying legal fees, let's get one thing straight. A lot of new entrepreneurs mix up registering their business name (like an LLC or a DBA) with getting a federal trademark. They’re completely different.

Registering your business with the state just gives you the green light to operate legally under that name within your state. That’s it. It offers almost no brand protection and does nothing to stop someone in the next state from using the same name.

A federal trademark, however, is all about brand ownership on a national scale. It protects your identity—the name, logo, or slogan your customers recognize—in all 50 states.

Unpacking the Core Differences

To make the right call, you need to know exactly what you're getting with each type of protection. A simple business registration is a local administrative task; a trademark is a strategic investment in your brand's future. I’ve seen too many business owners learn this the hard way, long after a competitor has swooped in and claimed their name in another market. For a deeper dive on state-level requirements, you can check out our detailed guide on how to register business names.

And this isn't just a local issue. The competition for brand protection is fierce globally. Not long ago, worldwide trademark applications hit about 15.2 million in a single year—a number that's been skyrocketing since 1990. This just goes to show how essential trademarks have become for anyone trying to build a unique identity in a crowded market. You can find more data on this global trend over at Statista.com.

Key Takeaway: Registering your LLC protects your personal assets from business debts. Trademarking your business name protects your brand from being copied. They serve two totally different purposes.

It's easy to get these legal protections confused. This quick comparison should help clear things up so you can decide what’s right for your business.

Trademark vs Business Registration vs Copyright: A Quick Comparison

Protection Type | What It Protects | Governing Body | Geographic Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

Federal Trademark | Brand Identity (Name, Logo, Slogan) | U.S. Patent & Trademark Office (USPTO) | Nationwide |

Business Registration | Right to Operate Legally | State Government (e.g., Secretary of State) | State-Specific |

Copyright | Original Creative Works (Art, Music, Writing) | U.S. Copyright Office | Federal |

Ultimately, understanding these distinctions is the first step toward building a brand that's not just creative, but legally defensible for the long haul.

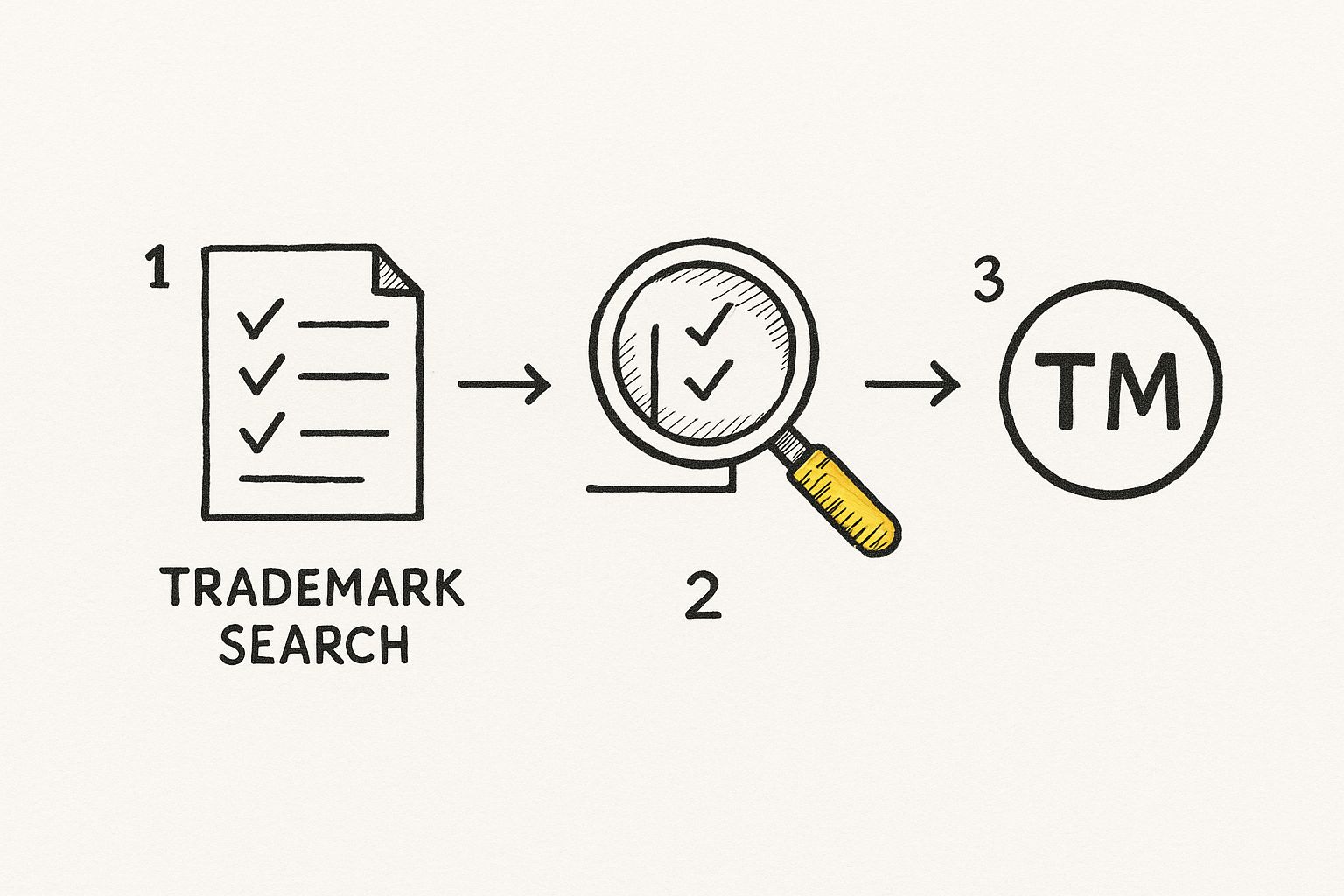

Conducting a Comprehensive Trademark Search

Before you even think about filling out a trademark application, you need to do your homework. Seriously. This is the single most critical step, and skipping it is the fastest way to get your application rejected by the USPTO, wasting both time and money.

Think of it like this: you wouldn't build a house without surveying the land first. A proper trademark search is your survey. You're not just looking for an identical name; you're looking for anything that could cause a conflict down the road. The goal is to uncover potential problems now, not after you’ve already invested in your brand.

This whole process is about digging deeper at each stage to make sure the name you love is truly available.

As you can see, a good search moves from the federal level all the way down to how a name is being used in the real world, ensuring you cover all your bases.

Your First Stop: The USPTO TESS Database

The official starting line for any search is the USPTO's Trademark Electronic Search System (TESS). This is the federal government's master list of all registered and pending trademarks.

But a simple search for your exact name won't cut it. You have to get creative and think like the attorney who will eventually review your file. This means hunting for:

Different spellings

Names that sound the same (phonetic equivalents)

Phrases that give off a similar vibe or commercial impression

For example, if your name is "Kwik Fix," you absolutely have to search for "Quick Fix," "Kwik Ficks," and anything else that sounds alike. TESS has advanced search tools that can help you cast a wider net to catch these sneaky conflicts.

Real-World Examples That Trip People Up

It's one thing to talk about this in theory, but let's look at some real-world scenarios. Trademark conflicts are rarely black and white, and what seems like a clear path can be full of legal potholes.

Phonetic Similarity: Let's say you want to trademark "SunRise Coffee." A quick search for that exact phrase shows nothing. Great, right? Not so fast. A deeper dive reveals a registration for "Son-Rise Coffee Roasters." Because they sound identical, the USPTO would almost certainly flag this for a likelihood of confusion and reject your application.

Cross-Industry Conflict: A tech startup lands on the name "Apex" for their new software. They check Class 9 (the category for software) and find it's wide open. The problem? They didn't realize 'Apex' is a world-famous registered trademark for hand tools in Class 8. Since the Apex tool brand is so well-known, the USPTO could argue that customers might think the software company is related to the tool giant, even though they're in totally different industries.

(Counter-Intuitive) Acquired Meaning: You stumble upon a registered trademark for "The Sofa Company" and think, "How is that possible? It's just descriptive!" Well, after years of exclusive use, heavy marketing, and building a solid reputation, that name has gained what's called secondary meaning. Consumers now connect that name to one specific business, which makes an otherwise generic name protectable.

Looking Beyond the Federal Database

Just because you're clear on TESS doesn't mean you're home free. You've still got to check for state and "common law" trademarks.

State Trademark Databases: Every state has its own trademark registry. A business in California might have a state-level trademark that never shows up in the federal TESS database. You'll need to check the Secretary of State website for every state you plan to do business in.

Common Law Searches: In the U.S., you can get trademark rights just by using a name in commerce, without ever formally registering it. This means you have to become a bit of a detective. Search Google, social media handles, and business directories. Checking for available domain names is also a huge part of this. Our guide on how to check domain availability walks you through how to do this effectively.

Expert Insight: Always remember the legal standard here is "likelihood of confusion." The question isn't whether the names are identical, but whether the average customer would get confused about who is providing the product or service. Search with that customer's perspective in mind.

A Simple Search Framework

To keep yourself organized and make sure you don't miss anything, you can follow this tiered approach. This is all about building a strong, confident case that your name is legally sound.

Search Layer | Where to Look | What to Look For |

|---|---|---|

Federal Level | USPTO TESS Database | Exact matches, misspellings, phonetic equivalents, similar commercial impressions. |

State Level | Secretary of State Websites | Registered trademarks in key states of operation. |

Common Law | Google, Social Media, Domain Registries | Unregistered uses of the name, especially within your industry. |

By methodically working through each of these layers, you’ll drastically improve your odds of a successful application. More importantly, you'll secure a brand name that you can confidently own and build for years to come.

Choosing the Right Trademark Class for Your Business

Here's one of the most common—and costly—misunderstandings I see with new business owners: they think trademarking their name gives them a monopoly over it. They believe once it's registered, no one else can use it. Anywhere. For any reason.

That’s just not how it works.

A trademark only protects your name within specific categories of goods or services, known as International Trademark Classes. Think of these classes like aisles in a supermarket. You can trademark "Apex" for your line of fresh bread in the bakery aisle (Class 30), but that doesn't stop someone else from using "Apex" for car tires over in the auto aisle (Class 12).

The whole system is designed to prevent customer confusion within a particular market. Nailing down the right class isn't just a box to check; it’s a critical part of protecting your brand.

A Simple Framework for Identifying Your Classes

Before you get overwhelmed by the 45 different classes, let's simplify. I always advise clients to think about their business from the inside out.

Start with your core offering. What’s the main thing you sell? If you have a t-shirt brand, you’re starting in Class 25 (Clothing). If you're a financial consultant, your home base is Class 36 (Insurance and Financial Services). Simple.

Now, what about related products? Let's say you run a coffee shop. Your primary service—making and serving coffee—falls under Class 43 (Restaurant Services). But you also sell branded mugs (Class 21) and bags of your signature coffee beans (Class 30). Each of those needs its own class.

Finally, think about the future. Where is your business headed in the next few years? If your skincare line (Class 3) has a wellness app on the roadmap, you should probably think about filing for Class 9 (Software) sooner rather than later.

Pitfalls and Gotchas to Avoid

Navigating these classes can feel a bit like a minefield. Here are a few common mistakes that can leave your brand exposed.

Being too broad. You can't just file in a class to "reserve" it for later. You have to prove you’re either already using your name for those goods or have a genuine "intent to use" it. Speculation doesn't count.

Choosing the wrong class entirely. This is an instant rejection. If you file for "business consulting" (Class 35) but what you actually sell is downloadable software (Class 9), your application won't even get off the ground. Be precise.

Forgetting about digital goods. This trips up a lot of people. An author selling physical books (Class 16) who also launches an online course needs to file in Class 41 for educational services. For more on this, our guide on the strategic naming of products has some great insights.

Expert Insight: Remember, you pay a government filing fee for every single class you add. While it's tempting to cast a wide net, it's far more strategic (and budget-friendly) to focus only on the classes that are directly relevant to what you're doing now and in the very near future.

Caselet: Artisan Eats Bakery

Let me tell you about a small bakery, "Artisan Eats." They filed a trademark for their name and correctly identified their core business—baked goods—so they filed in Class 30. A year later, a competitor launched a line of baking mixes called "Artisan Feasts."

Because Artisan Eats had no protection for things like mixes or prepared foods (Class 29), their hands were tied. By the time they filed a new application to add that class, the competitor was already established. It was a costly lesson in foresight.

Real-World Examples of Strategic Class Selection

This isn't just theory. The data shows exactly where the battles for brand ownership are being fought. The Madrid System, which handles international trademarks, processed nearly 65,000 applications recently. The most crowded category? Class 9 (for computer hardware and software), making up 10.8% of all filings.

Here’s how this plays out in practice:

The SaaS Company: A business with a project management software tool (a service) files in Class 42 (Software as a Service). But if they start offering in-person workshops, they'll need to add Class 41 (Education and Training) to protect that revenue stream.

The Clothing Brand: An apparel company selling t-shirts and hats is firmly in Class 25 (Clothing). The moment they launch a popular podcast about fashion, they need to file in Class 41 to protect their brand name in the entertainment world.

The Fitness Influencer: This is a classic "edge case." An influencer builds a huge following with workout videos and meal plans, so they trademark their name in Class 41 (Entertainment/Education). Then, they launch a line of branded protein powder. That requires a totally separate filing in Class 5 (Pharmaceuticals and supplements)—a category they probably never even considered when they first started.

Filing Your Trademark Application with the USPTO

https://www.youtube.com/embed/A_xEWeG0GAc

Alright, you've done the hard work of searching the database and figuring out your trademark class. Now it’s time to make it official by filing your application. This happens on the USPTO's Trademark Electronic Application System (TEAS), and it's where the rubber really meets the road.

Think of this as more than just filling out a form. You’re building a legal case for your brand, arguing why it deserves federal protection. Every field you complete has legal significance, and a simple mistake can get your application bounced. The goal is to file a “clean” application that sails through without getting an “Office Action”—that’s the official letter from the USPTO telling you there’s a problem.

TEAS Plus vs. TEAS Standard: Which Form Should You Use?

First things first, you have to pick your application form. The USPTO gives you two main choices, and this decision impacts both your wallet and your workload.

TEAS Plus: This is the budget-friendly, streamlined option. The filing fee is lower (currently $250 per class), but it comes with stricter rules. You have to pick your description of goods or services from the USPTO’s pre-approved list and agree to handle all communication electronically. It's a bit like ordering from a set menu.

TEAS Standard: This form offers more flexibility but costs more (currently $350 per class). This is your go-to if what you sell is unique and doesn't quite fit the pre-written descriptions. You can write your own custom description here, but be warned—this is where many applications go wrong.

Honestly, for most businesses, TEAS Plus is the smarter move. It forces you to use clear, pre-vetted language, which dramatically cuts down the chances of an examiner kicking it back for being too vague.

Nailing the Goods and Services Description

This section is the absolute core of your application. It defines the precise scope of legal protection your trademark will have. You need to be specific, accurate, and leave no room for ambiguity.

A Pro Tip From Experience: Don't get clever or try to be overly broad here. Saying you offer "business services" will get you nowhere. You need to be specific, like "Business consulting services in the field of marketing and brand strategy." The more precise you are, the less friction you'll encounter.

If you’re on the TEAS Plus form, this part is fairly simple since you’re just choosing from a dropdown list. But if you’re using TEAS Standard and writing your own, triple-check it for clarity. A poorly written description is one of the fastest ways to get an Office Action and delay your registration for months.

The Make-or-Break Role of the Specimen

If you’re filing based on "use in commerce"—meaning you're already using the name to sell stuff—you have to provide a specimen. This is your real-world proof. It’s not a mockup or a concept; it's evidence that your brand is out there in the market. This is a classic stumbling block for first-timers.

A good specimen shows your trademark directly tied to what you're selling.

For physical goods (like apparel or coffee): A photo of a product tag, the branded packaging, or the item itself with the name clearly on it works great. An invoice or a shipping label? Not so much. Those don't count.

For services (like consulting or a SaaS platform): A screenshot of your website, a marketing brochure, or an ad where the trademark is used while offering the service is perfect. The key is showing a direct link between the name and the service being sold.

Real-World Example: How a Bad Specimen Derails an Application

Let’s look at a new e-commerce store, "Zenith Wares." They filed to trademark their name for selling custom-printed mugs. For their specimen, they uploaded a screenshot of their internal inventory spreadsheet, which listed "Zenith Wares Mugs" next to their SKU numbers.

The result? A quick rejection via an Office Action. The USPTO examiner explained that an internal document doesn't show "use in commerce" because a customer would never see it.

The fix: They had to resubmit with a proper specimen—this time, a clear photo of a mug inside its branded box, ready to be shipped. The application was then approved, but that simple mistake cost them four months.

Your Final Pre-Flight Checklist

Before you hit that submit button and enter your credit card info, take five minutes to run through this one last time. This quick review can be the difference between a smooth registration and months of headaches.

Who's the Owner? Is the applicant listed correctly? Make sure it's the right legal entity (you as an individual, your LLC, your corporation, etc.).

What's the Mark? Did you specify if it's a standard character mark (just the words) or a special form mark (a logo with design elements)?

What Do You Sell? Is your description of goods and services perfectly aligned with the class(es) you chose?

Where's the Proof? If you're filing as "in-use," is your specimen a valid, customer-facing example?

Any Generic Words? Did you disclaim any generic terms in your mark? For example, if your mark is "APEX COFFEE," you'd need to disclaim the exclusive right to use "COFFEE" by itself.

Is it Signed? Make sure the application is signed by someone with the legal authority to act on behalf of the owner.

The TEAS application is all about attention to detail. By understanding these key pieces and knowing where the common traps are, you give yourself the best possible shot at getting your trademark registered without a hitch.

So, You've Filed. What Happens Now?

Hitting "submit" on your trademark application feels great, doesn't it? It’s a huge step. But I have to be honest with you—this is where the real waiting game begins. Your application has just been dropped into the queue at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), and it’s going to be a while.

The first part of the journey is just silence. You're waiting for an examining attorney to be assigned to your file, and this alone can take several months. Their job is to put your application under a microscope to make sure it follows all the rules and doesn't step on any existing trademarks.

Navigating the Examination and Bumps in the Road

Once an examiner finally gets to your application, it can go one of two ways. In a perfect world, they approve it for publication. But more often than not, you’ll get something called an Office Action in your inbox.

Don't panic. An Office Action isn't a flat-out rejection. It’s a formal letter from the examiner outlining problems they found. Some are simple to handle, while others are much more serious.

Easy Fixes: These are usually procedural hiccups. Maybe you need to disclaim a generic word in your name (like "Cafe" in "Starbright Cafe") or tweak the way you described your services.

The Big Hurdles: These are substantive refusals, and they're trickier. The most common one by far is a "likelihood of confusion" refusal. This means the examiner thinks your name is too close to an already registered trademark. Getting past this requires a solid legal argument, not just a simple correction.

You'll have six months to respond to an Office Action. If you miss that deadline, your application is considered abandoned. This is a critical point where many people who file on their own get into trouble, as crafting a persuasive response often takes a bit of legal know-how.

The Publication Window: Your 30-Day Test

Let's say you clear the examination hurdle. Congratulations! Your mark is then published in the USPTO’s Official Gazette. This starts a 30-day publication period.

Think of it as a public comment period. During these 30 days, anyone who believes your trademark could harm their business can file a formal opposition to your registration. It's not something that happens every day, especially for smaller businesses, but it's a possibility you should be aware of. If that 30-day window closes without any opposition, you’re on the home stretch.

Pro Tip: From the day you file to the day you get your registration certificate, expect the process to take anywhere from nine months to well over a year, and that's if things go smoothly. You absolutely have to keep an eye on your application's progress using the USPTO's Trademark Status and Document Retrieval (TSDR) system.

Keeping Your Trademark Alive for the Long Haul

Getting your trademark registered is the goal, but it’s not the end of the story. A trademark isn't a "set it and forget it" asset; you have to actively maintain it to keep your legal rights intact.

The brand landscape is more crowded than ever. Just to give you an idea, the U.S. recently saw a 9.1% jump in trademark filings in a single year, with a 25% spike in applications from foreign entities. This shows you how fierce the competition for a unique brand name is. You can dig deeper into these global trademark filing trends on Clarivate.

To keep your registration valid, you have mandatory check-ins with the USPTO:

Declaration of Use: Between the fifth and sixth anniversary of your registration, you must file a sworn statement proving you are still using the trademark.

Renewal: After that, you have to renew your trademark every ten years.

Miss these deadlines, and your registration will be canceled. All that hard work will be for nothing, and your brand will be vulnerable again. Understanding how to trademark a business name means committing to its long-term care.

Got Questions About Trademarking Your Business Name?

If you're diving into the trademark process, you've probably got questions. It's a journey filled with nuances, and getting clear on the details upfront can save you a world of headaches (and money) down the road. Let's tackle some of the most common questions I hear from entrepreneurs just like you.

How Much Does It Really Cost to Trademark a Business Name?

There's no single price tag. The total cost to trademark a business name usually lands somewhere between $500 and $2,000, but that number is a mix of a few different things.

USPTO Filing Fees: This is the non-negotiable part you pay directly to the government. You’re looking at $250 per class for the streamlined TEAS Plus application, or $350 per class if you need the more flexible TEAS Standard form.

Attorney Fees: You can file on your own, but hiring a trademark attorney dramatically boosts your odds of success. They've seen it all. A lawyer might charge a flat fee—often $500 to $1,500—for the whole search and application package, or they could bill by the hour.

Future Costs: Don't forget what comes later. If the USPTO sends back an "Office Action" with questions or objections, you'll need to pay to have it answered. And there are mandatory maintenance documents to file years down the line to keep your trademark alive.

Can I Trademark a Name That Is Already in Use?

This is a classic "it depends." It all comes down to who used the name first, where they used it, and what they used it for. In the U.S., you can establish trademark rights just by using a name in commerce, even without filing a thing with the government. These are called "common law" rights.

So, if another business is already using a similar name for similar products in their city, they likely have priority rights in that geographic area. You might get a federal registration, but you could be legally blocked from using your name in their territory.

The Bottom Line: If another business has a federally registered trademark or their name is genuinely famous, you're almost certainly out of luck. This is exactly why a thorough, professional-level search isn't just a suggestion—it’s the most critical first step you can take.

What’s the Difference Between the ® and ™ Symbols?

They look similar, but they mean very different things in the eyes of the law. Using them correctly is non-negotiable.

The ™ Symbol: Think of "TM" as "trademark." Anyone can use this symbol to put the world on notice that they're claiming a name as their brand. It's like planting a flag. You don't need to have filed any paperwork; it's just a way of saying, "Hey, this is mine!"

The ® Symbol: This one has real legal teeth. It means your trademark has been officially approved and registered by the USPTO. You can only use the ® symbol after your registration certificate is in hand. Using it before then is a big no-no and can jeopardize your application.

Once you’re officially registered, putting that little ® next to your name gives you major advantages, like the power to sue for infringement in federal court and potentially collect serious damages.

Real-World Examples to Bring It All Home

Theory is one thing; seeing how these rules play out in the real world is another. Here are a few scenarios that show just how tricky—and interesting—trademarks can be.

The Hyper-Local Business: Imagine a beloved bakery, "Sweet Caroline's," that's been operating in a single town for 20 years with no federal trademark. Someone across the country could potentially register "Sweet Caroline's Confections" for an online cookie business. The original bakery's common law rights are probably limited to its local area, opening the door for a similar name in a different market.

The Generic Name That Became Famous: When Booking.com first applied for a trademark, they were refused because "booking" is a generic word. But they didn't give up. They spent years on marketing and were able to prove that consumers overwhelmingly connected the name with their specific service. They won their case by showing the name had acquired "secondary meaning," making it protectable.

The "Edge-Case" of Surnames: You typically can't trademark a name that is "primarily merely a surname," like "Smith's Consulting." But there are exceptions. Aaron Bird was able to trademark "Bird" for his electric scooter company because "bird" has another common meaning in the dictionary. It wasn't just a surname.

Ready to find a brand name that’s not just catchy, but legally protectable? The journey of how to trademark a business name starts with a great, available name. Let the AI-powered tools at Nameworm generate unique ideas, check domain availability, and give your brand the strong foundation it deserves. Discover your perfect name today at Nameworm.ai.